Jedziemy straszliwie zatłoczoną drogą A82 na południowy zachód. Po drodze mijamy twierdze, pola walk, zamki szkockich klanów i siedziby miliarderów (najbogatszym człowiekiem w Szkocji jest Duńczyk, własciciel firmy ASOS). Mijamy też różnych idiotów, którzy tuż obok mają ścieżkę rowerową, ale wolą zginąć pod kołami…

We’re driving southwest along the horribly congested A82. Along the way, we pass fortresses, battlefields, Scottish clan castles, and billionaire residences (the richest man in Scotland is a Dane, the owner of ASOS). We also pass various idiots who have a bike path right next to them but they prefer to die under the wheels …

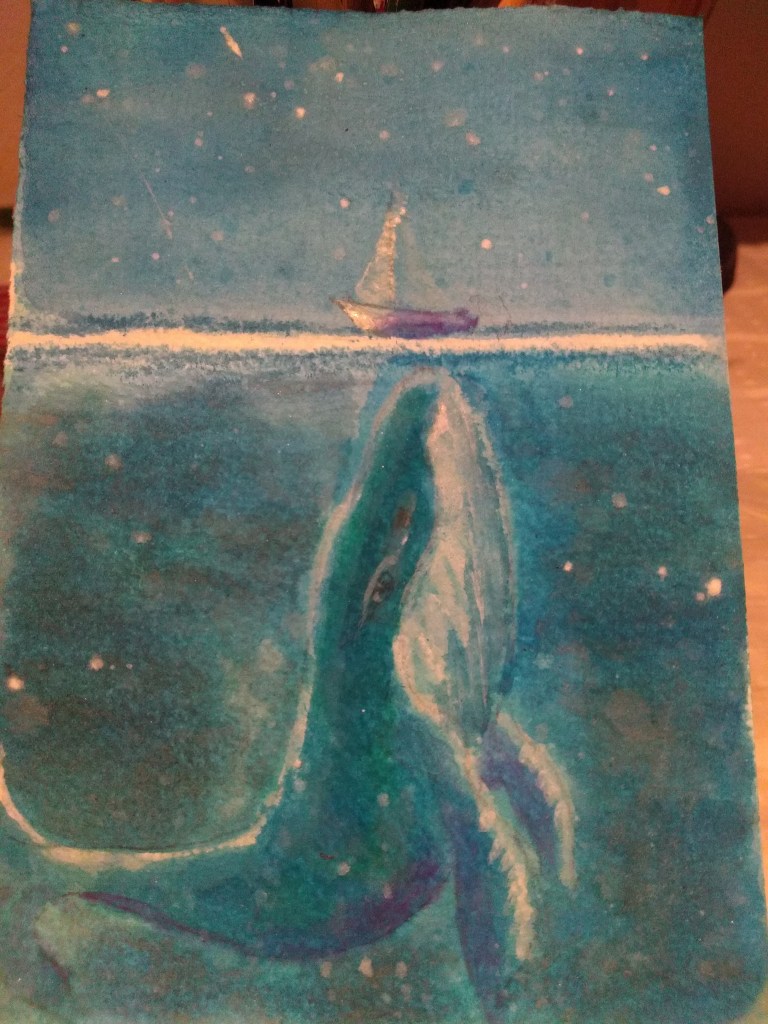

Zmierzamy do zamku Urquhart (Caisteal na Sròine), a właściwie ruin leżących na zachodnim brzegu najbardziej znanego jeziora na świecie – Loch Ness. Jezioro jest wąskie, ale ma około 37 kilometrów długości. Jest też niesamowicie głębokie (w najgłębszym miejscu ma 227 metrów!), a jego wody są ciemne i ponure… Jak wiecie w jeziorze mieszka legendarna istota, rozpalająca wyobraźnię od VI wieku i przynosząca Szkocji ogromne dochody. Nie będę pisać o Nessie, bo wystarczy obejrzeć film „Koń wodny”, w którym wszystko jest wyjaśnione (Film „Koń wodny: legenda głębin” z 2007 roku).

We’re heading to Urquhart Castle (Caisteal na Sròine), or rather ruins, lying on the western shore of the world’s most famous loch – Loch Ness. The loch is narrow, about 37 kilometers long. But it’s incredibly deep (at its deepest point, it’s 227 meters!), and its waters are dark and gloomy. As you know, the loch is home to a legendary creature, one that has captured the imagination since the 6th century and brought Scotland a huge income. I won’t write about Nessie, because in the movie „The Water Horse” everything is explained (the 2007 film „The Water Horse: Legend of the Deep”).

Jezioro jest otoczone górami, słodkowodne, polodowcowe, a jego wody zawdzięczają swój ciemny kolor torfowi. Po prawie godzinie możemy wysiąść z autokaru i powędrować w dół wieloma schodami na błonia zamku Urquhart.

Surrounded by mountains, the lake is freshwater, glacial, and its waters owe their dark color to peat. After almost an hour, we disembark the coach and hike down the many steps to the grounds of Urquhart Castle.

Ruiny zamku nie robią na mnie wielkiego wrażenia. Mamy lepsze na Szlaku Orlich Gniazd, ale widok stąd na jezioro jest fantastyczny. Sam zamek powstał w 12 wieku, a jego historia odzwierciedla szalone dzieje Szkocji – bitwy, klanowe walki o wpływy, wojen o niepodległość i szkockich powstań przeciwko Koronie. Od 17 wieku stopniowo zamieniał się w ruinę, obecnie należy do National Trust for Scotland. Z przystani można popłynąć stateczkiem do Dochgarroch Lock czy Fort Augustus, albo po prostu popływać po jeziorze w poszukiwaniu Nessie.

The castle ruins don’t impress me much. We’ve seen better ones on the Eagle’s Nest Trail, but the view of the lake from here is fantastic. The castle itself was built in the 12th century, and its history reflects Scotland’s frenetic history—battles, clan power struggles, wars of independence, and Scottish uprisings against the Crown. Since the 17th century, it has gradually fallen into ruins and is now owned by the National Trust for Scotland. From the pier, you can take a boat to Dochgarroch Lock or Fort Augustus, or simply cruise the lake in search of Nessie.

Ostatnie spojrzenie na Loch Ness i wracamy do portu Invergordon bocznymi drogami, wzdłuż wrzosowisk, sosnowych lasów, niewielkich pastwisk i wielkich destylarni. Jutro wypływamy.

One last look at Loch Ness and we return to Invergordon Harbor via back roads, past heathland, pine forests, small pastures, and large distilleries. We sail tomorrow.