To była jedna z najdziwniejszych wojen w historii, a opowiadam o niej z punktu widzenia Islandii, dla której morze i jego zasoby decydowały o jej istnieniu. / It was one of the strangest wars in history, and I tell it from the point of view of Iceland, for which the sea and its resources determined its existence.

Rozdział pierwszy: 1958 – 1961 Pierwsza Wojna Dorszowa

Chapter One: 1958 – 1961 The First Cod War

Z powodu zmniejszenia się liczebności ryb na Północnym Atlantyku, Islandia ogłasza powiększenie swojej strefy przybrzeżnej z 4 do 12 mil morskich. (z ok. 7,5 do 22 km). Strasznie wkurzyło to Brytyjczyków, którzy od ponad dziesięciu wieków wyprawiali się na wody przybrzeżne Islandii, żeby łowić tam wielkie ilości dorszy (potrzebne do narodowej potrawy „fish and chips”). Stwierdzili, że mają zakaz w dupie i w towarzystwie czterech okrętów wojennych (!) dwadzieścia trawlerów pojawiło się w rejonie Westfjords. Jak wiecie Islandia nie ma armii, nie mówiąc o flocie wojennej, a Brytole nasyłają jedną z największych flot wojennych na świecie na kilka kutrów islandzkiej Straży Przybrzeżnej! Jak napisał historyk Guðni Jóhannesson; „tylko okręt flagowy Þór (Thor) mógł skutecznie zatrzymać i, w razie potrzeby, odholować trawler do portu”.

Niemal natychmiast stało się jasne, że brytyjska potęga militarna będzie trudną do pokonania przeszkodą dla narodu islandzkiego. Dlatego zwrócono się ku dyplomacji. Najpierw Islandia zagroziła wystąpieniem z NATO, jeśli jej roszczenia do wód terytorialnych nie zostaną uszanowane. Następnie politycy obiecali wydalić wszystkie siły amerykańskie stacjonujące na Islandii. Przypominam, że trwała „zimna wojna”, a na Islandii stacjonowały wojska NATO.

Due to a decline in fish stocks in the North Atlantic, Iceland announces an expansion of its coastal zone from 4 to 12 nautical miles (from approximately 7.5 to 22 km). This greatly infuriated the British, who for over ten centuries had been venturing into Iceland’s coastal waters to fish for cod (needed for the national dish, „fish and chips”). They decided they didn’t give a damn, and, accompanied by four warships (!), twenty trawlers appeared in the Westfjords. As you know, Iceland has no army, let alone a navy, and the British are sending one of the world’s largest naval fleets against a few Icelandic Coast Guard cutters! As historian Guðni Jóhannesson wrote, „only the flagship Þór (Thor) could effectively stop and, if necessary, tow a trawler to port.” Almost immediately, it became clear that British military might would be a difficult obstacle for the Icelandic people to overcome. Therefore, they turned to diplomacy. First, Iceland threatened to withdraw from NATO if its claims to territorial waters were not respected. Then, politicians promised to expel all American forces stationed in Iceland. Remember, the Cold War was raging, and NATO troops were stationed in Iceland.

Konferencja Narodów Zjednoczonych w sprawie Prawa Morza w latach 1960–1961 przyniosła następujące rozwiązanie – Islandia miała prawo do utrzymania swoich wód terytorialnych, pod warunkiem, że Wielka Brytania będzie mogła prowadzić połowy na określonych obszarach i w określonych porach roku. Umowa przewidywała również, że wszelkie dalsze spory między Islandią a Zjednoczonym Królestwem dotyczące praw połowowych będą rozstrzygane przez Międzynarodowy Trybunał Sprawiedliwości w Hadze.

Przez pewien czas między wyspami panował pokój. Jednak nie na długo.

The 1960–1961 United Nations Conference on the Law of the Sea resulted in the following outcome: Iceland had the right to maintain its territorial waters, provided that the United Kingdom could fish in certain areas and during certain times of the year. The agreement also stipulated that any further disputes between Iceland and the United Kingdom regarding fishing rights would be resolved by the International Court of Justice in The Hague.

For a time, peace reigned between the islands, but not for long.

Rozdział drugi: 1972 -1973 Druga Wojna Dorszowa

Chapter Two: 1972 -1973 The Second Cod War

Drugi rozdział konfliktu o prawa połowowe rozpoczął się we wrześniu 1972 roku. Islandia ponownie podjęła decyzję o rozszerzeniu swoich wód terytorialnych, tym razem do 50 mil morskich. W ten sposób dążyła do ochrony swoich zasobów rybnych i zwiększenia swojego udziału w połowach dokonywanych wokół Islandii. Nic dziwnego, że Wielka Brytania ponownie wyraziła sprzeciw, podobnie jak członkowie Układu Warszawskiego i wszystkie inne państwa Europy Zachodniej. W rzeczywistości tylko państwa afrykańskie poparły ekspansję Islandii, twierdząc, że jest to skuteczny sposób na zwalczanie zachodniego imperializmu.

The second chapter of the conflict over fishing rights began in September 1972. Iceland again decided to expand its territorial waters, this time to 50 nautical miles. This move sought to protect its fish stocks and increase its share of the catch around Iceland. Not surprisingly, Great Britain once again expressed opposition, as did the Warsaw Pact members and all other Western European states. In reality, only African states supported Iceland’s expansion, arguing that it was an effective way to combat Western imperialism.

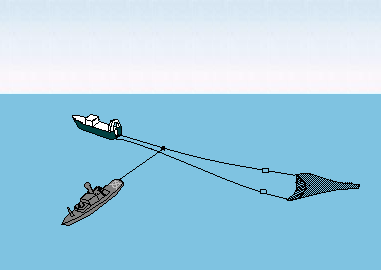

Podczas drugiej wojny dorszowej Islandia zmieniła taktykę. Zamiast próbować holować brytyjskie trawlery, zdecydowała się przecinać ich sieci rybackie, używając nożyc do sieci. Strategia ta początkowo przynosiła duże sukcesy. Przykładem może być sytuacja, gdy okręt wojenny ICGV Ægir napotkał nieoznakowany trawler. Islandczycy poprosili o szczegóły dotyczące pochodzenia trawlera, ale ich prośba została wysłuchana jedynie poprzez odtworzenie w eterze pieśni „Rule Britannia”. W odpowiedzi ICGV Ægir przeciął cumy trawlerów, co wywołało ostrą wymianę zdań między obiema załogami. Brytyjscy marynarze rzucali w niego nie tylko przekleństwami…

During the Second Cod War, Iceland changed tactics. Instead of trying to tow British trawlers, it decided to cut their fishing nets using net cutters. This strategy initially met with considerable success. For example, the warship ICGV Ægir encountered an unmarked trawler. The Icelanders requested details of the trawler’s origins, but their request was answered only by playing „Rule Britannia” on the airwaves. In response, the ICGV Ægir cut the trawlers’ mooring lines, sparking a heated exchange between the two crews. The British sailors hurled not only curses at it…

Rozdział Trzeci: 1975 – 76 Trzecia Wojna Dorszowa

Chapter Three: 1975-76 The Third Cod War

Wielka Brytania i Islandia po raz ostatni rywalizowały ze sobą, tym razem od 1975 roku. Brytyjskie rybołówstwo podupadło już w połowie lat siedemdziesiątych. Z tego powodu ten konkretny spór z Islandią wydawał się znacznie bardziej zacięty niż wcześniej.

W 1973 roku większość państw uczestniczących w Konferencji Narodów Zjednoczonych ds. Prawa Morza zgodziła się na limit połowów wynoszący 100 mil morskich. Islandia jednak nie była usatysfakcjonowana i zdecydowała się na limit dwukrotnie wyższy niż wcześniej ustalony. Wielka Brytania ponownie odmówiła uznania decyzji Islandii.

The UK and Iceland last competed against each other, this time in 1975. British fishing had already been in decline by the mid-1970s. Because of this, this particular dispute with Iceland seemed much more heated than before. In 1973, most nations participating in the United Nations Conference on the Law of the Sea agreed to a 100-nautical-mile fishing limit. However, Iceland was not satisfied and opted for a limit twice that previously established. The United Kingdom again refused to recognize Iceland’s decision.

Jedno z największych wydarzeń konfliktu miało miejsce w grudniu 1975 roku. Islandzki statek Straży Przybrzeżnej, V/s Þór, odkrył trzy brytyjskie trawlery – każdy trzy razy większy niż islandzki kuter. Na rozkaz odpłynięcia trawlery udawały, że wykonują polecenia, jednak po kilku milach okręty zaczęły celowo skręcać w stronę islandzkiego statku. Islandczycy odpowiedzieli strzałami ślepymi, a następnie ostrą amunicją. V/s Þór zmienił kurs, aby uniknąć staranowania, ale był niebezpiecznie bliski zatonięcia. W odpowiedzi Królewska Marynarka Wojenna wysłała 22 fregaty i siedem statków zaopatrzeniowych. Jednak nawet w obliczu tak wielkiej przewagi Islandczycy kontynuowali walkę. Do końca wojny odnotowano łącznie 55 incydentów taranowania.

W lutym 1976 roku Islandia podjęła decyzję o zerwaniu stosunków dyplomatycznych ze Zjednoczonym Królestwem. Rząd Islandii wyraźnie zasugerował również, że wystąpi z NATO, jeśli nie uda się osiągnąć wyznaczonych celów. Ostatecznie to zagrożenie zadecydowało o wyniku wojny. Amerykanie naciskali na Brytyjczyków, aby zakończyli konflikt, ale to Islandia po raz kolejny wyszła z niego zwycięsko.

Islandia osiągnęła swoje cele. W rezultacie, i tak już podupadające brytyjskie rybołówstwo zostało mocno dotknięte wykluczeniem z historycznie najlepszych łowisk, a duże północne porty rybackie jak Grimsby, Hull i Fleetwood podupadły.

One of the biggest events of the conflict occurred in December 1975. The Icelandic Coast Guard vessel, V/s Þór, discovered three British trawlers—three times the size of the Icelandic cutter. When ordered to depart, the trawlers pretended to obey, but after a few miles, the vessels began deliberately turning toward the Icelandic vessel. The Icelanders responded with blank shots and then live ammunition. V/s Þór changed course to avoid being rammed, but came perilously close to sinking. In response, the Royal Navy dispatched 22 frigates and seven supply ships. However, even in the face of such overwhelming odds, the Icelanders continued to fight. By the end of the war, a total of 55 ramming incidents had been recorded. In February 1976, Iceland decided to break diplomatic relations with the United Kingdom. The Icelandic government also strongly suggested it would withdraw from NATO if its stated goals were not achieved. Ultimately, this threat determined the outcome of the war. The Americans pressured the British to end the conflict, but Iceland emerged victorious once again. Iceland achieved its goals. As a result, the already declining British fishing industry was severely affected by being excluded from historically prime fishing grounds, and large northern fishing ports like Grimsby, Hull, and Fleetwood declined.

Bilans tej wojny to zwycięstwo Islandii nad Wielką Brytanią w kwestii prawa do połowów na północnym Atlantyku, w wyniku których Islandia rozszerzyła swoją wyłączną strefę ekonomiczną (EEZ) i umocniła swoją suwerenność morską. No i nikt nie zginął.

The outcome of this war was Iceland’s victory over Great Britain for fishing rights in the North Atlantic, which resulted in Iceland expanding its exclusive economic zone (EEZ) and strengthening its maritime sovereignty. And no one was killed.

Dziękuję za materiały Reykjavik Maritime Museum. No i Magdzie, Ani i Piotrowi za zainteresowanie 🙂 / Thank you to the Reykjavik Maritime Museum for the materials. And to Magda, Ania, and Piotr for their interest 🙂